ADD is on the Rise: Yoga Can Help

Yoga as a Bridge: Navigating Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) through Mindful Movement and Meditation Practices - By Lizzie Emly

Reading time: 4 minutes

Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) is getting a lot of media attention. While the raised awareness is a good thing, the downside is that it’s sort of become a ‘condition du jour’, a buzz word (or buzz acronym), so much so that it’s almost difficult to verbalise that you, or someone you love, has ‘it’: the response could be anything from an eye roll to an enthusiastic reassurance that, actually, we all have ‘a bit of that’. Characterised by a distortion of focus, impulsive behaviour and presenting with or without hyperactivity, ADD is thought to affect around 4% of the population, with many believing that the true incidence is much higher.

The increased noise is almost certainly related to the sharp increase in diagnoses over the past few years. Interestingly, the largest increase is within the adult population, possibly because for many of those with the condition (often women), it manifested as inattentiveness without the hyperactivity commonly associated with ADD (hence the differentiation between ADHD and ADD). This group flew under the radar, struggling in areas of executive functioning but without causing the kind of disruption that would lead to intervention, and thus remaining undiagnosed. This was my own experience, suspected only when going through the process of my very hyperactive daughter’s assessment. The realisation, as an adult, that there was a possible explanation behind my apparent inability to make decisions, complete a task in a methodical and timely fashion, or organise my bills/ admin/ passport renewal appropriately came as a relief. However, it also brought a sadness that had I known sooner, I may have been better understood and better supported.

One thing for which I am enormously grateful is that I had an outlet: I loved to dance, and in spite of the difficulty I sometimes had in learning sequences, I danced well. Looking back, I believe that it was my saving grace. The ability to get into my body and move was a relief from the anxiety I was plagued with. Considering how often I described dancing as ‘time off’ from thinking, I wonder if it wasn’t the case that, for me, dancing was equivalent to moving meditation. This notion came to me when reading Gabor Mate’s acclaimed book ‘Scattered Minds’. One sentence in particular caught my attention: ‘All traditional meditative and contemplative practices.. have as their purpose helping us to disengage for a time from our concerns with people, objects, desires, thoughts and fears, to actively strive for connection between ourselves and the rest of creation’. I felt that this sentence captured precisely something which I had never been able to put into words. I can’t tell you what I was ‘thinking’, but I know that when I danced, my brain and body were engaged and that in those moments I felt, well, the only way I can describe it is ‘free’.

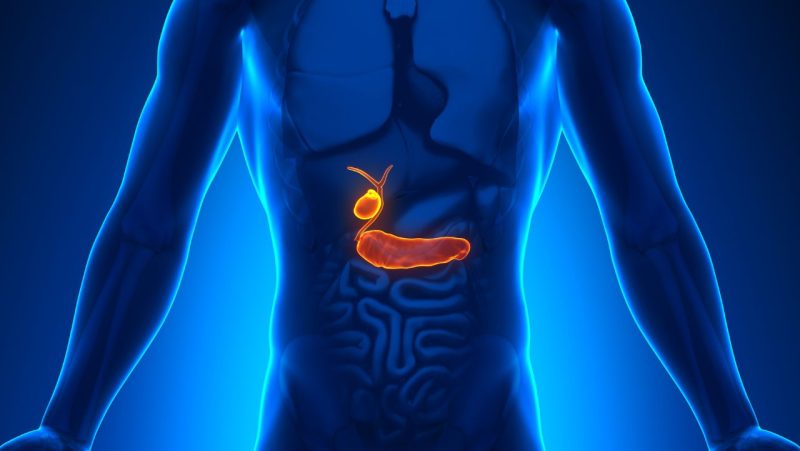

The meditative practices referred to in ‘Scattered Minds’ are what Mate describes as ‘contemplative solitude’. Meditation in the traditional sense of the word is often presented as one good option for managing ADHD symptoms. The practice is understood to act upon the pre-frontal cortex, an area of the brain which plays an important role in impulse control and focus, and can therefore be wonderfully helpful. However, for many people with the condition (and probably without), the very thought of sitting in stillness for so much as half a minute is enough to make them run a mile. Clearing your mind is a nice idea, but when your brain feels like the biological equivalent of the 140 tabs open on your phone, letting go is nothing less than a major operation. Thus ‘sitting down to meditate’ remains number 100 on the mental list of 100 things the day will be spent flitting between. This, I believe, is where yoga can act as a bridge between the everyday chaos that can be the reality of out-of-control ADD, and a place of greater clarity where there is space for the natural gifts of the individual to flourish.

One of the key characteristics of ADD is attention distortion which often presents as the inability to focus. Yoga asana practice requires the attention to be taken to breath and body. As the focus is directed or oscillates between these, somewhere between the movement and moments of stillness, exists a place where the over busy mind naturally relinquishes. Balancing postures illustrate this point well: it is hard to either think about a million and one things, or to lose concentration entirely, when you are committed to not falling over. You must be present but not distracted. You must find steadiness. For the same reason, balances are considered excellent for anxiety, another feature of ADD, and this principle can be applied to all postural yoga (though admittedly without the added pressure of avoiding a broken ankle or risking your dignity). The internal dialogue diminishes because the attention is directed towards the breath, towards following cues, finding postures and holding or moving through the posture. There’s a lot going on but it’s going on intentionally and mindfully. The result of this guided and specific movement practice is evident by the end of the class: Savasana feels an entirely different experience in both mind and body from laying on your back cold.

The practice of moving mindfully further supports the individual’s emotional regulation, an essential tool in managing impulsivity. The more we practice the better we become at ‘tuning in’, and recognising and observing our inner experience; the sensations we feel, the changes or asymmetries we notice and the emotions that come up. To begin with, this may be as simple as feeling the shoulders drop, or actively listening to the hamstrings in a stretch, but over time we get good at noting the subtleties and knowing our own bodies, physically and emotionally. The practice of noticing leads to acknowledgement, and when we acknowledge, perhaps giving language to, our sensations and feelings, we give ourselves the time and opportunity to explore what is going on, and to make a choice about how we frame the situation and respond. Frustrations and judgments can become curiosity and compassion. Eventually it is possible to take the practice of listening to our internal landscape and carry it into many of the other day-to-day settings we find ourselves in.

I’m inclined to think, though, that the hardest challenge for those with ADD is actually committing to a yoga practice. To those who say that moving meditation is, by definition, a slow practice, I am going to be bold and argue that anything which engages the participant enough to get on the mat and stay there is the best place to start. It may be true that slow movement gives us more time to decipher nuances within the mind and body, and accomplish steadiness of mind. This could be a goal to strive towards. However, for lots of people with ADD who are inexperienced in meditation, slow equals free reign for the wandering mind. Surely, then, it is better to start with something captivating enough, whatever that may be, and work from there. Although they do require a degree of fitness, Ashtanga or Vinyasa yoga could be ideal options. Sun Salutations are perfect for consolidating the seamless flow of breath body movement, and the sequence incorporates numerous postures which bring attention to different muscle groups. This has the potential to set in motion the beginning of a mindful practice.

It has taken me many years of practicing yoga to reach a point of choosing to meditate in stillness, but there was a time when I wasn’t of the opinion that I would ever ‘meditate’ or practise ‘mindfulness’. I didn’t realise I was (albeit without the key ‘acknowledgment’ aspect) in a way, doing it all along, and that it had been a natural response to a condition I didn’t know I had. So if for the ADD mind sitting or moving slowly for meditation is too much of a stretch, then why not let the meditation reach the ADD mind in a way that it can progress with? The cultivation of any mindful practice seems a good place to start; with consistency that road will inevitably lead somewhere, and that can only be a good thing.