Darshan and ways of seeing

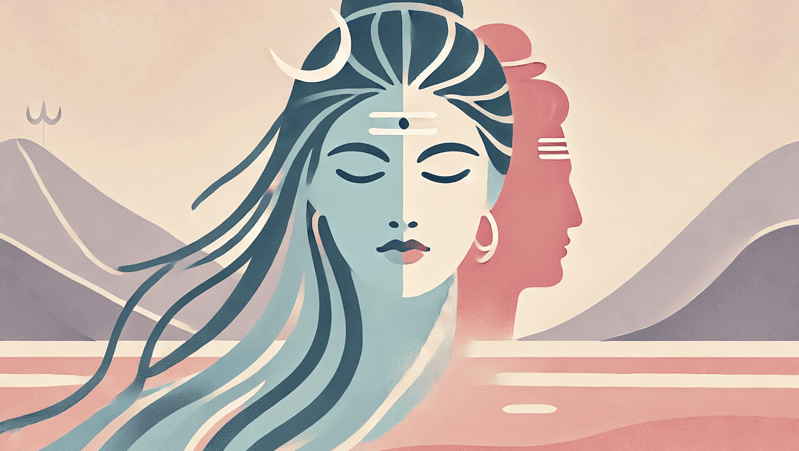

According to tradition, yoga in its many facets was revealed to ancient sages called rishis by none other than Lord Shiva – himself the greatest yogi. The word rishi comes from Sanskrit ṛṣi meaning ‘to see’. However, in India and many other cultures, ‘seeing’ is semantically not limited to ocular perception, rather it encompasses more broadly the notion of knowing - By Anna Freud

Reading time: 4 minutes

Anyone who has travelled to or is familiar with the subcontinent will recognize that India is a very visual culture – seeing lies at the very heart of its life and especially worship. The huge eyes of the gods meet those of their devotees in every temple and roadside shrine facilitating what is called darshan. Literally ‘seeing’, darshan is often translated as ‘auspicious sight’ of the divine but it could probably be more aptly understood as communion, or rapprochement if you like. Because darshan, as Diana Eck explains, means ‘seeing’ and ‘being seen’ (1998). It is an interaction. And although you will hear worshippers say they go to ‘take darshan’ (‘darśan lenā’), it is as much taken as it is given (‘darśan denā’). Through icons or holy men, prayers are sent and blessings received.

One of the most well-known depictions of darshan in Indian literature is contained within the Bhagavad Gita book of the Mahabharata where, in response to the devotee’s pleadings, Krishna reveals his cosmic form to Arjuna. To allow for the divine viewing, however, the warrior is first equipped with special eyes. In this way, vision is expanded from single sense perception to a deeper and broader form of knowing. It is interesting to note that in Hindu tradition eyes are not only the final part of any divine image making process, they are subject to ceremonial opening with a golden needle or the final stroke of a paintbrush. This is because eyes enable “psychical contact,” to use Jan Gonda’s words, and are “a means of participating in the essence and nature of the person or object looked at” (1969).

Artistic expression of darshan comes in many different forms, typically through the media of painting, lithography and sculpture. One of interesting new formats is contained within the Bhagavad Gita Experience at the Vedic Museum of ISKCON Temple in Delhi, India. Using spectacular dioramas, animatronics, and marvellous light and sound effects across eight rooms, key teachings of the most revered Hindu scripture are delivered through full body-mind immersion. The famous scene in which Lord Krishna unveils his cosmic form to Arjuna and facilitates unparalleled darshan is equally grand within the exhibition. The larger-than-life head of the god avatar is but the backdrop to even more prominent eyes which change their aspect as the scene unfolds in an attempt to recreate the feeling tone of Arjuna’s experience.

In ancient times, wisdom received through such visionary experiences would then be recorded in verse – poetry being the best tool for oral transmission and image recreation. This idea of seeing as knowing would later develop into six major schools of thought in Indian philosophy, called darshanas: Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta. It is important to note that rather than competing ideologies, these are viewpoints which present truth from their respective angles. And "any ‘point of view’ implicitly assumes that another point of view is possible.” (Eck, 1998). They are lenses through which to look at reality. They are ways of seeing. As Betty Heimann (1964) beautifully put it,

“Whatever Man sees, has seen or will see, is just one facet only of a crystal. Each of these facets from its due angle provides a correct viewpoint, but none of them alone gives a true all-comprehensive picture. Each serves in its proper place to grasp the Whole, and all of them combined come nearer to its full grasp. However, even the sum of them all does not exhaust all hidden possibilities of approach” (1964).

A take away message for everyday life? Seeing is not always literal, knowing comes in many forms, and points of view are just that. Diversity does not have to be ranked, it just has to be acknowledged. And we can all learn something from one another.

References:

Eck, D.L. (1998), “Darśan. Seeing the divine image in India” (New York: Columbia University Press)

Gonda, J. (1969), “Eye and gaze in the Veda” (The Netherlands: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts & Sciences)

Heimann, B. (1964), “Facets of Indian Thought” (London: George Allen & Unwin)