Planet Yoga

Is it possible to ‘be in the moment’ while our world burns? by Jo Benn

It can be hard to read environmental news without feeling depressed. Having worked in the field for almost 20 years, part of me feels exhausted and numb, while the rest is incredulous. Why are we able to measure our demise to the nearest carbon molecule stored in an oak tree, yet apparently incapable of acting collectively to prevent it?

To take one example, the first six months of this year saw a record-breaking heat-wave in the Siberian Arctic, with temperatures more than 5°C above average. This melted permafrost, made buildings collapse, and sparked an unusually early and intense start to the forest fire season. Scientists have shown that climate change caused by humans has made such dangerous outcomes at least 600 times more likely.

It’s not just happening in the far north of Russia. Last year’s heat-wave at Bodega Bay in California roasted mussels in their shells. Heat-exhausted bats fell dead from trees across Australia amidst apocalyptic scenes of burning houses, smoke-filled forests and cremated creatures. Species are dying in unprecedented numbers, and humans might join them one day unless something changes soon.

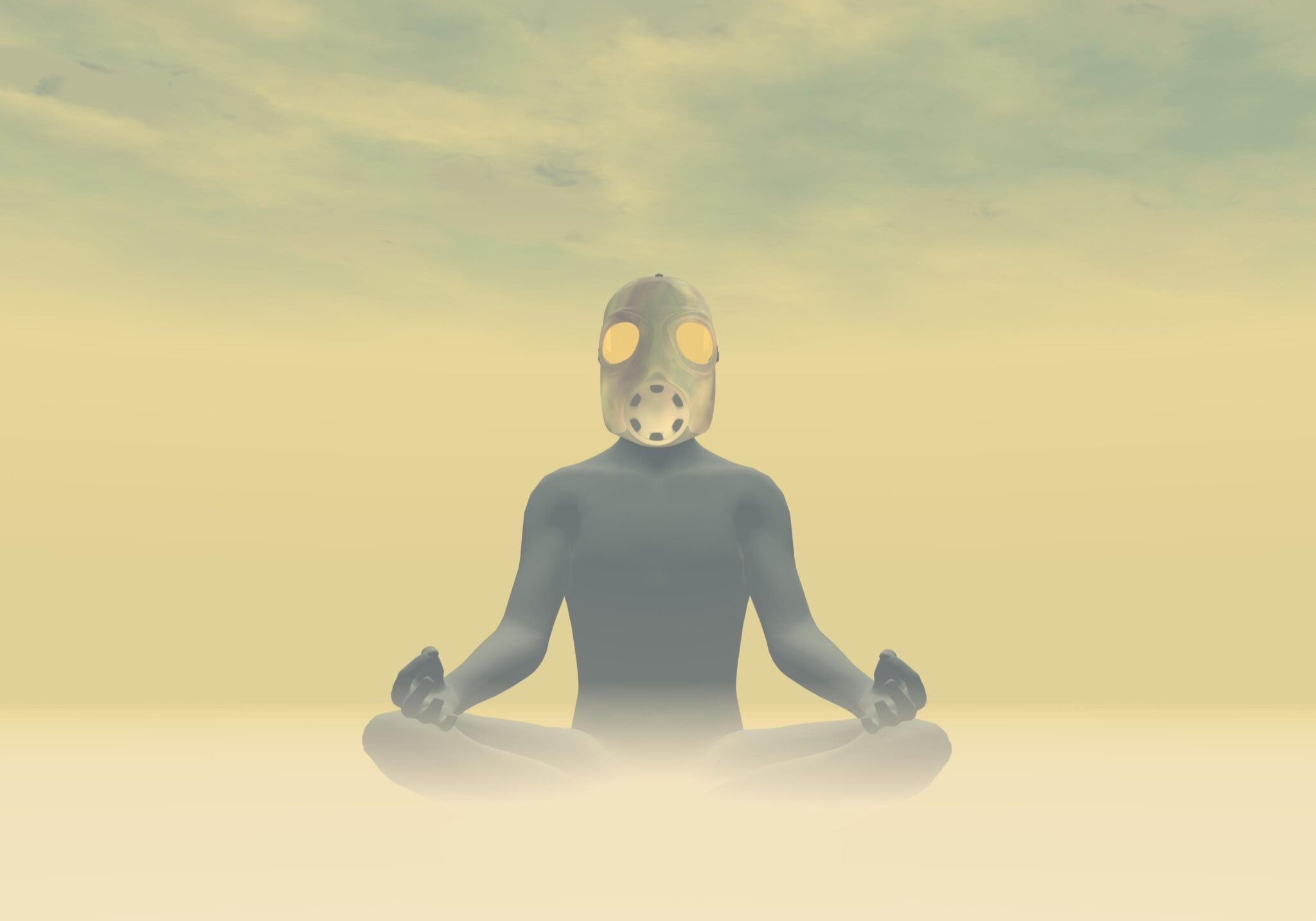

As an advocate for environmental protection and also a yoga teacher, I find it challenging to reconcile both worlds. The practice of yoga involves introspection and a general acceptance of things as they are, while solving environmental crises requires radical action. I increasingly wonder if there might be connections between the two that we might profitably explore. By changing our mindset and becoming more conscious, might we build resources that help us to cope and eventually act? Or are we just tuning out in feel-good bubbles?

What happens next?

Climate activists are always facing deadlines. Yet it’s almost impossible to overstate the importance of the next 10 years. If we reduce carbon emissions by at least 50 per cent by 2030, we still have a chance of avoiding the worst impacts of climate change. Waste it, and the future looks bleak. We are reaching irreversible tipping points. Cross them and runaway feedback effects will amplify, warming until the planet is ‘largely uninhabitable.’

How does yoga fit into this picture? We all have our own roles to play in life – socially, politically, and ultimately spiritually. And the highest objective in all these domains is to free ourselves and others from pain and suffering. In yoga, we speak of our dharma – the path to be followed by each individual in ways that are harmonious with the whole.

Dharma is simultaneously the eternal order that rules the universe and the duty or law that governs one’s life. Fulfilling one’s dharma is more than simply one’s purpose – it is considered the very means by which one transcends the cycle of birth and death, or what is known as saṃsāra. Another important term is karma, which means action. For every action there is also a reaction, and the cycle of cause and effect spans endless lifetimes. Acting in accordance with dharma provides a release from this karmic spiral – or in other words, by helping each other we can transcend misfortune.

I would argue that to be fully present to our common humanity, we need to acknowledge the inherent unfairness of global climate change. It is one of the greatest injustices inflicted on the poor in the last few centuries, and it exacerbates the problem of widening inequality. Wealthier people and countries whose lifestyles cause much more environmental damage can afford to buffer themselves against the impacts. We also seem blind to overlapping crises. The United Nations has warned that as governments find ways to tackle the disaster of Covid19, we are only so far treating the health and economic symptoms, not its underlying cause, which is related to destructive patterns of food supply, energy creation and infrastructure location.

If our dharma is to care, we must first know and understand what is happening – and its deadly karmic consequences. Acting blindly – or ignoring how our lives affect the planet we depend on – must surely undermine our dharmic duty, limiting our chances of freedom from cycles of karma.

Truth and non-harming

Mohandas Gandhi built his political philosophy out of the first two ethical precepts of Patañjali’s yoga – ahiṃsā (often translated as non-violence) and satya (truthfulness). Many other texts about dharma have named these ideas as essential foundations. If we claim to love all beings – to feel compassion for every soul – can we really say with hand on heart that enjoying our pleasures at a cost to others is ‘right action’? We need to consider how our consumption, our travel, our food and leisure choices all have an impact on fellow humans, domestic animals and wildlife, and the natural world itself.

I would argue that to be fully present to our common humanity, we need to acknowledge the inherent unfairness of global climate change.

As yoga practitioners, is it not incumbent on us to investigate and educate ourselves, and then make informed choices? It might not be easy to decipher the best course of action, but could it nonetheless be helpful to reflect on the importance of minimising harm? Perhaps we could ask ourselves simply: ‘What do I want to do in the world? Do I want to retrain in some way that can contribute more? How do I change my diet? Should I change my car?’ Although it’s true that merely engaging with our own carbon footprint won’t solve the whole problem, it’s a start that can shift our awareness.

We can also engage with the powerful structures that shape broader action; that means raising our voices, pushing corporations to go further and faster, and pressuring governments at all levels. That some people are voluntarily reducing their own emissions is a clear sign of our willingness to change – by flying less, eating less meat and dairy (the biggest source of emissions from food) and using clean energy. Another yoga truism – ‘Where we focus attention – it goes.’

What we do is materially important. More than 11,000 scientists have said ‘clearly and unequivocally’ that we are facing a climate emergency that could bring ‘untold suffering’ without major changes in how humans live. People sense this already. I’m often asked where one might move to avoid rising sea-levels; whether London will go underwater; if it’s right to have more children; and perhaps most commonly – and desultorily – ‘why bother trying if it’s getting too late to stop it happening?’

It’s scary to acknowledge the reality that millions – perhaps even billions – of us could die from the effects of extreme heat in the decades ahead. Our chances are largely determined by where we live and the local consequences of today’s economic disparities. And yet we still have some agency.

A mindful pause, not disconnection

We mustn’t turn away from our current situation despite feeling overwhelmed and disempowered. Yes, we practise yoga to feel better. To feel more in our bodies, healthier, calmer, and fitter. But isn’t there more? In āsana practice, we move from one pose to another, we take time to re-align and then transition to the next pose – finding our balance and a focused gaze, or dṛṣṭi, before taking action.

In yoga, we breathe and move with intention. We actively control our breath to control our minds in search of focus and clarity. Yet what are we breathing? Air pollution levels remain dangerously high in many parts of the world. New data from WHO shows that 9 out of 10 people breathe air containing high levels of pollutants. WHO also estimates that a staggering 7 million people die every year from exposure to polluted air.

In more recent news, a team of 25 scientists recently narrowed the window of how hot the world will get. known as climate sensitivity. The assessment, conducted under the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) supports a likely warming range of between 2.6°C and 3.9°C. To put that in context – every fraction of a degree count. By 2100, global sea level rise would be 10 cm lower with global warming of 1.5°C compared with 2°C. The likelihood of an Arctic Ocean free of sea-ice in summer would be once per century with global warming of 1.5°C, compared with at least once per decade with 2°C. Coral reefs would decline by 70-90 percent with global warming of 1.5°C, whereas virtually all will be lost with 2ºC.

The new, narrower estimate for climate sensitivity has huge implications, not just for climate science, but for how humanity prepares for a warming world. It shows that the worst-case scenario is not quite as dire as previously thought, but also that the best possibilities are still grim. In particular, it means that it will be almost impossible to hit the main target of the U.N. Paris climate agreement – limiting warming to less than 2°C (3.6 °F) this century. Our only hope is concerted action to reduce emissions with even less margin for delay.

We cannot hope to fumble our way through the next few decades without first pausing to look at the options and honestly accepting how much has to change in the coming ten years. Satya and science can be married. Science tells us that we can see the planet and our impact on it in more detail than ever before. Satya says we must look without flinching at the fact that we are permanently changing and wreaking the Earth and its ecosystems. In just a few decades our generation has released enough CO2 to fundamentally reshape the biosphere for millennia. What we do now doesn’t just affect everyone and every species alive today, but also those that may live in the next many thousands of years.

“We need a real awakening, enlightenment, to change our way of thinking and seeing things. To breathe in and be aware of your body and look deeply into it, realise you are the Earth and your consciousness is also the consciousness of the Earth.” Thich Nhat Hanh