Saving Sanskrit Manuscripts

India’s rich scriptural heritage, which has given the world the knowledge of yoga and meditation, is at risk of being destroyed by climate change.

Written on palm-leaf scrolls, these centuries-old manuscripts cannot withstand the havoc wrought by human activity and global warming. Some small charities are working tirelessly to save endangered scriptures from being lost to the world forever. But, it is time for all of us to become aware of the potential loss of the sacred wisdom contained in these fragile manuscripts, and help save the past for the spiritual benefit of future generations of the world.

During the annual monsoons in India last year, the ground floor of a 150-year old library, crammed with books from floor-to-ceiling, was completely inundated. For three whole days, 40,000 old books were submerged under eight feet of water, reducing them all to pulp. Along with the library’s precious collections of old books were many rare, handwritten manuscripts that dated back several centuries, all of which disintegrated in the water.

While there has been growing global awareness about the calamitous loss of plant bio-diversity and animal species due to the combined causes of human activity, global warming, and climate change, the loss of the world’s scriptural legacy, due to the very same causes, has been far less examined.

India has a very long and illustrious history of sophisticated spiritual thought. It is, after all, the country that has shared with the world the secrets of yoga, meditation, and Ayurveda. Many of these profound metaphysical musings on the nature of man and God, were inscribed on scrolls made from palm leaves.

Palm Leaf Scrolls

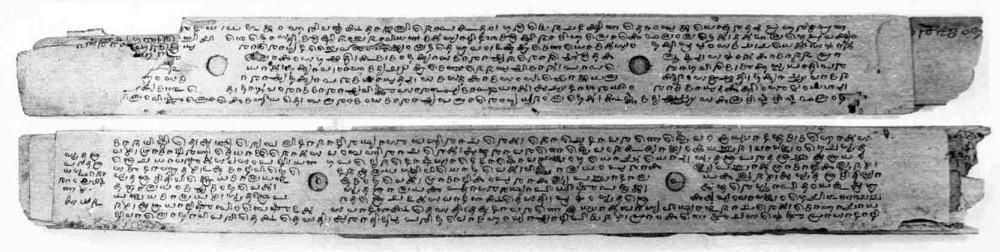

While elsewhere in the world, vellum, papyrus, or paper was used for writing, in India and south Asia, the preferred material for writing was the palm-leaf scroll.

For centuries, individual palm leaves, were dried, cured, then cut into rectangular shapes, and made ready for writing on. Letters were inscribed with a knife-like pen on to these palm-leaf scrolls. Colourings were applied across the surface and subsequently wiped off, leaving the ink in the incised grooves to reveal the inscribed text. A string passed through holes in each page was then tied together to make books.

Such palm-leaf scrolls, with their distinctive rectangular shapes, were used from ancient times right until the 19th century. Each scroll could last anywhere from just a few decades to 600 years, before falling victim to dampness, insect activity, mould, and human handling.

The organic material in these scrolls inevitably deteriorated with the passage of time. Made from plant carbohydrates, they were vulnerable to the environmental effect of sunshine, humidity, as well as infestations of insects, silverfish, mould, and other biological factors. Natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, as well as man-made ones such as wars and the destruction of libraries and temples where these scrolls were housed, also contributed to the loss of valuable manuscripts.

One of the oldest surviving Sanskrit collections of manuscripts on palm leaves is the Pārameśvaratantra

One of the oldest surviving Sanskrit collections of manuscripts on palm leaves is the Pārameśvaratantra, a Shaiva Siddhanta text dating from the 9th-century CE. Shaiva Siddhanta is one of the Tantric theological schools that taught the worship of Shiva as ‘Supreme Lord’ (the literal meaning of ‘Parameśvara’). Dated to about 828 CE, the palm-leaf scroll is held by the University of Cambridge Library.

Although the Pārameśvaratantra is so far unpublished, a digitised copy exists in the digital library of the Muktabodha Indological Research Institute (www.muktabodha.org) as part of its Shaiva Siddhanta collection. This small not-for profit organisation is dedicated to the digital preservation of India’s scriptural heritage, in particular the texts of Kashmir Shaivism, Shaiva Siddhanta, and the Vedas. It makes all collections in its digital library freely available to scholars and seekers throughout the world.

The Beauty of IT

For centuries, temples, libraries and families tried to safeguard their scriptural collections by using traditional methods of preservation. These included the use of indelible ink in the re-copying of texts, wrapping palm-leaf scrolls in cotton dipped in turmeric water, and exposing manuscripts to sunlight on special days during the solstices when the rays of the sun were considered to contain special anti-microbial qualities.

Today, digital technology offers far greater security for the preservation of the past. First of all, it is not subject to the merciless vagaries of the weather. Furthermore, it offers greater scope for digital dissemination. This, in turn allows for a global study of the philosophical thought contained within these endangered manuscripts. With everything available at the click of a button, no longer do scholars and researchers have to displace themselves or trudge to far-flung and often inaccessible temples, monasteries, and libraries, to look for ancient texts. In fact, the free and easy dissemination of the contents of rare texts to every corner of the world at all times, as offered by Muktabodha and other such charities, has encouraged the study of India’s great philosophical legacy across the continents.

In the second half of the 20th century, the European colonial powers granted independence to their colonies, and left – but not before taking away many rare and important works of art, artefacts, books and manuscripts. Today, thanks to digital technologies that enable the preservation and dissemination of information, it is no longer necessary to dispossess owners of their heritage collections in order to study or examine their history and culture. Instead, these technologies allow original sources such as books, manuscripts, and artefacts to remain with their rightful custodians, while preserving their contents should those sources be accidentally destroyed, and making them available to the world.

So let us, by all means, save the pandas and the rainforests – but let us also use cutting-edge technology to safeguard the knowledge and wisdom of the past for the benefit and well-being of future generations!