The obsession with doing it ‘right’ in yoga

How many cues to perfection: the obsession with doing it right in yoga. By Katia Shulga

I’m on a jetty, on a clear early autumn evening with the sun setting over the lake. The wind is still and the rays of the sun reflect in the mirror of the lake washing everything with a warm orange glow. I take out my yoga mat and roll it out on the wooden boards of the jetty. I have some time to practice in this beautiful environment, how lucky!

“It’s like you’re inside Instagram right now,” I hear my inner voice. “You should be loving this. Shame you can’t do a headstand, or something else fancy.”

My body is creaky as I move it from one pose to the next, my breath shallow. “What’s up with your breath? Not very yogic that. You need to practice breathing more.”

As I attempt to pick poses that loosen up my stiffness, I feel myself getting more tense with every move.

“You should really do something more strength-based. How’s that foot alignment? Is your hip bone correctly in the socket?” I keep adjusting minuscule details in every pose.

And then I stop…and I wonder: “When did yoga become so complicated?”

That sticky rectangle on which we practice is a place where we get to know ourselves, and knowing ourselves often means discovering who we are.

Whatever pattern you have off the mat, often appears on the mat. This was my need for perfectionism slowly creeping in.

Yet, there is a dual influence going on here. Yes, it is my innate need for a right and a wrong, and a desire to ‘get it right’.

But, there are also the countless voices in the yoga world declaring what is right and wrong.

This particular pattern — wanting to ‘get it right’ — is a sneaky one, especially because it matches some of what yoga is about.

When we think of the famous and possibly traditional yoga teachers, such as B.K.S. Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois, of course there is a ‘this is how you do it’ approach.

But also in the modern yoga world. Each style has its own solution to what ails us; it’s all about either the bone alignment, or the muscular engagement, or the breath, the fascia, the vagus nerve and so on.

More and more specialised trainings are available. So, as teachers and even as practitioners, we move from one training to the next, trying to integrate this vast amount of knowledge in the hope of ‘getting it right’.

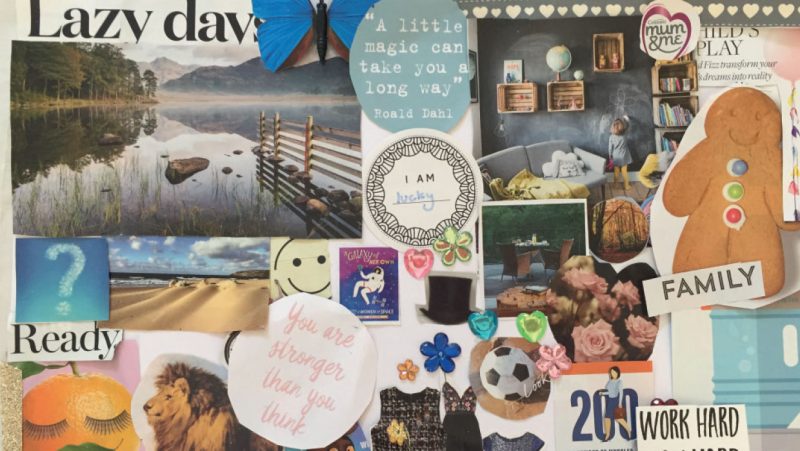

And then of course the Instagram phenomenon.

This visual aspect to yoga has created a whole world where what it looks like is more important than what it feels like.

Yoga can be visually impressive, but those impressive poses are often hard-won with years of dedication and emerge after many, many ‘boring’ poses. It can be impressive, yet at the same time it says nothing about the person’s practice, only about their athleticism.

I used to think a headstand was impressive, now it feels like you need to be doing a handstand scorpion touching your head with your feet — and preferably on the edge of a cliff with a sunset setting over the mountains and the northern lights emerging just above!

When I started practicing yoga, I kept going back because it felt so good. I felt so relaxed and clear afterwards. I didn’t really think much about what I was doing in the class, I just did it. I followed the instructions and went home feeling good. It was simple.

This was only about 14 years ago, yet in yoga terms it was a lifetime ago.

I remember buying a DVD to practice at home; there was one magazine from the US and not much else around. Instagram was definitely not a thing.

So in a way, I was left alone to ‘feel’ the experience of yoga. But as the industry progressed, so did I, hungry to learn more. With a natural desire to learn, but also to be the best, to be perfect, to get the instructions just right, my practice started binding me to rules instead of giving me more freedom, as it used to do.

Some of it is my doing — my own need for safety in perfectionism. But some of it is the natural discipline that comes with old yoga traditions and the divisive and detailed nature of the new styles. The obsession with correct physical practice, with knowing anatomy to such fine detail that you’re doing each pose just right.

Yet, if you study any of it, you learn that there is no perfect pose, there is only your body and your own unique self that is changeable on each day.

Hearing all the voices in my head on that beautiful autumn evening I felt sad how far I’d gone with listening to each instruction as if it was the only truth.

The reality is that every piece of new research in anatomy, every new version or style of yoga are just different shades of the same thing. They’re not the truth. They’re an exploration and not a conclusion.

And so is the practice; it’s an exploration and not the final product, or the final pose. We can be grateful for all the new findings and instructions on ‘engage your serratus anterior’ or ‘send the hipbone back in space’ but we don’t have to become slaves to it.

If you’re anything like me, then these instructions feel comforting as you try to ‘get it right’, but really, would you rather ‘get it right’ or ‘feel good’?